My Amateur Memory Grid

This year I made the goal to memorize bigger chunks of Scripture. First I started with Psalm 16, following my usual method of repeated repetition. But after diving deeper into research about memory in the Medieval Age, I decided to try a different tactic for my next passage. I planned to use the memory grid—a memory system attributed mainly to 12th century scholastic Hugh of Saint-Victor. ((Parrott-Sheffer, C. (2020, February 07). Hugh of Saint-Victor. Retrieved July 08, 2020, from https://www.britannica.com/biography/Hugh-of-Saint-Victor))

Hugh’s memory grid uses what it sounds like—a grid. Each numbered box contains a set of words from the Scripture passage. These words and their specific places, colors, and the corresponding images and flourishes around them all work together as the person recalls the number, the box, and the text. This kind of system was certainly not the only memory method used in the medieval ages, but it—like many others—focused on the importance of visual cues and order.1

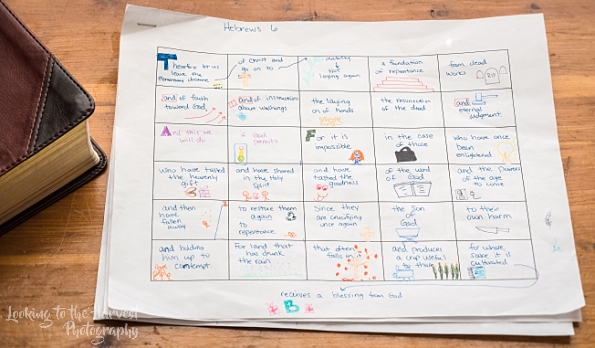

While my grids were not perfectly executed (I forgot to include numbers on my first paper!) the following is how I did it. I started with a blank 5 x 6 printed table. Next came the gel pens! I began to write and split up the chapter into each box—making sure to not go over seven words in one single box. I did this because the human brain can hold about seven items plus or minus two in its working memory at a time. (( Miller, George A. “The Magical Number Seven, plus or Minus Two: Some Limits on Our Capacity for Processing Information.” Psychological Review 101, no. 2 (April 1994): 343. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.101.2.343.)) This method of chunking into manageable items made it easier to keep in mind.

Once I filled my grid I went back through each box and added pictures to help me in my memorization. This part was challenging and fun. In some cases I drew pictures of exactly what was represented. “Produces a crop” became a row of corn, and “land that drinks the rain” was a picture of rain falling on grass. In other cases, I focused on words alone and what they sounded like. “In the case of those” had a picture of a briefcase, and “feel sure of better things” turned into a hand feeling a stick of butter!

My kids really enjoyed seeing my pictures and asking what they meant, and I found myself laughing along as I drew. And this is the key—for in memory techniques throughout history, the crazier the memory image—the more it sticks. Perhaps this is seen clearest in my (poor) drawing of the old cartoon Kim Possible for the word “Impossible.” I never even watched the show, but that silly thought came to mind, so I kept it.

For Hebrews 6 I worked one page of grid at a time and managed to create three separate grids from that one chapter. I hope to continue a few more chapters, but I’ll share with you so far what I’ve learned from this interesting experiment.

1. It was very different.

I’m so glad I was able to work through Psalm 16 in my regular way right before this, for I had the opportunity to compare the two processes. I found the memory grid so fascinating at how it challenged me. As I worked through several boxes at a time, I found it felt so different. Instead of reviewing and “hearing” the words, the memory grid used my visual senses so much more, as my brain worked to recreate the internal representations of the grid on my paper. It seems obvious, but I wasn’t expecting it to be quite as different as it felt!

2. It was easier.

To be honest, I found this method easier. Though it worked my brain in a different kind of way, I found it easier to place phrases and words in the right place. As I mentally moved through the rows of my grid, I didn’t stumble as much as I did in my previous memorization of Psalm 16. When I struggled through the Psalm, if I forgot the beginning of the next phrase, I sat stuck—waiting until it came to me. With the grid system, I had constant cues at my disposal, along with the rhythm of the words to help me. Once I really got the internal pictures in my head, I was able to race through the chapter. With repeated use, some pictures turned into indiscriminate blobs in my head, that I just knew were there. This was good, though at times I needed to go back slower and redefine those pictures.

3. It became more available

Another gift I personally found from this method was that it was a little easier for me to meditate on the verses. Instead of having to bring actual word phrases to mind, I could think of a box, and bring to mind that phrase and think it over. The pictures allowed me to highlight key words, even now sitting here, whereas, in my Psalm 16- I found it harder to isolate phrases in the middle of the text I memorized. (This is actually one neat thing that this kind of memorization system offered in the Medieval Ages- by this system, one could easily recite one line from different Psalms and pop easily back and forth between them. I did find I could do this pretty well in my own grid. I could start at any line I chose by “finding” the picture).

4. It still required work.

Sorry, but it’s true. I’ve shared a lot about the positive aspects of using this grid (and I do intend to use it to continue in chapter 7,8, and 9), but like anything, this method requires work. A common lie is that we can learn tricks to make memorizing easier, but that’s not the case. Barring physical gifting, the greatest of mental athletes must work at using their memory techniques just as the great memory-holders of the Medieval Age did.

While I do think that using the grid made it easier to retain my chapter, I still needed to practice it. Sometimes I had to keep correcting as I found that the images I put down were not enough, and on sticky words I’d add another image, or alteration to the box to help me remember what I kept forgetting. It required effort.

However we decide to get Scripture into our heart, the important thing is to do it. One of the greatest benefits this experiment has given me is just the opportunity to slowly sit in a large piece of Scripture for a long time. Every day new phrases held more meaning, and God showed me new connections. The goal of memory is not to check boxes but to delight in God’s Word.

Maybe a grid will help you do that, but maybe not. But let’s spur each other on to remember the sentences, the phrases, and the words of the Lord.

Below are some pages of my memory grid for Hebrews chapter 6. (No drawings are meant to represent Jesus himself).

** Additional clarification: Upon writing, I realized I didn’t note another difference in my use of the grid with the original use. In Hugh’s memory grid, the numbers of the boxes were the initial cues to all that the box contained. They were supposed to work like a file system. I found that my pictures became the cues rather than the numbers. I think this had more to do with how I memorized those to begin with, and what I focused on (probably this initially occurred because I forgot to even include numbers in my first page).

- Information sourced from Mary Carruther’s work on memory systems in the Medieval Age: Carruthers, Mary J. The Book of Memory: a Study of Memory in Medieval Culture. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013. [↩]